Moorcock had Roberts and Vinter to thank for purchasing the magazine in 1964. Soon Moorcock had what amounted to a free editorial reign. Within its cheaply printed pages readers could find stories by a cadre of these so-called New Wave writers, whether Tom Disch, Brian Aldiss, M. John Harrison, J.G. Ballard, D.M Thomas, or Moorcock himself. These writers were mostly young, neither baked in the cynicism of the genre nor aligned with its mainstream tendencies. Moreover, contributors were as likely to be influenced by Burroughs and Pynchon, as Sturgeon, Stapleton, PK Dick, Lieber or David Lindsay. As for those who read the magazine, they were sort who preferred perusing International Times and Tariq Ali’s Black Dwarf rather than the mainstream or traditional leftist press. Given New Worlds outsider status, it was inevitable that it would meet some resistance. One of its stories, Bug Jack Barron, by Norman Spinard, which appeared in a March 1968 New Worlds, so outraged those in certain quarters that it led to a ban on the magazine’s distribution stretching from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to WH Smiths in the UK, not to mention a debate in the British Parliament regarding the misuse of Arts Council funding, which had been, to a large degree, subsidising the magazine.

If not flying its proverbial freak flag, New Worlds was doing its best to move against the tide of sci-if technocrats- no point mentioning names- whose space operas and stories of planetary expansionism and futurist war games had long dominated the genre. Not quite a case of anything goes, for Moorcock and his followers it was more a matter of transforming old tropes and creating new ones. All of which was coincident with the interest, thanks to psychedelics and soft drugs, in expanded consciousness, inner rather than outer space, as well as individual freedom. As Moorcock himself said, it was a time “when we let the rockets explore the multiverse in terms of the human psyche. Powered by a faith that fiction- especially speculative fiction- could change the world, the New Wave allied with the underground press, the left, and the world of rock ‘n’ roll to create a cultural explosion.” Moreover, in keeping with the politics of the era, Moorcock, in 1969, was not only beginning to think of New Worlds as a magazine of experimental literature as much as speculative fiction, but decided, whether of his own volition or by the persuasion of others, to democratise his editorship, and allow others to take on some of the editorial responsibilities. Which could have been a sign that the magazine was running out of revolutionary steam. Indeed, it would never quite recover, even though New Worlds would continue for some years, eventually, to publishers Sphere and Corgi, morphing into a periodic paperback anthology.

Meanwhile, in the U.S. the energetic and seemingly ever youthful Harlan Ellison was churning out his Dangerous Visions anthologies, beginning with a Doubleday edition in 1967. As excellent as the stories in Ellison's anthologies were- a sign of Ellison's acumen as an editor- the books were never, as far as I was concerned, quite as radical a departure from mainstream science fiction as were the stories found in New Worlds. It could be the authors who appeared in the pages of Ellison's paperback were a bit more established, as might befit the demands of a mass market paperback publisher. But that didn't mean that they didn't attract a legion of readers, myself included, who picked them up wherever and whenever they appeared. Most likely in liquor store and bus station paperback racks or on newspaper stands rather than in legitimate book stores. It was at one such liquor store on Haight Street in San Francisco that I came across Ellison’s first anthology. That book, and their follow-ups, functioned, for me, as a kind of entry level drug, providing me with my first taste of Zelazny, Leiber, Delaney, and PK Dick’s mind-bending Faith of Our Fathers, a story with which I soon became obsessed. The stories were all accompanied by Ellison's pithy and evocative intros- just a few sentences to prepare the reader for their deep dive into each particular vision. Yet those anthologies lacked the same immediacy as New Worlds, nor did they have the explicit intention to, in Moorcock’s words, “create a cultural explosion.” Still, they were necessary for those seeking something more mind expanding than what science fiction was accustomed to serving up at the time. Ellison’s series would continue into the 2000s, but it was that first handful of editions that appeared from 1967-69 that were, for me, the most interesting. Or it could simply be that their contributors were, whatever their past output, fairly new to a neophyte reader as I was at the time. Interestingly, there was a degree of cross-over between the two publications. British writers such as Aldiss and John Brunner would appear in Ellison’s publications, while American writers like Spinard, Ellison, Delaney, John Sladek, Rachel Pollack and Pamela Zoline would crop up in the pages of New Worlds.

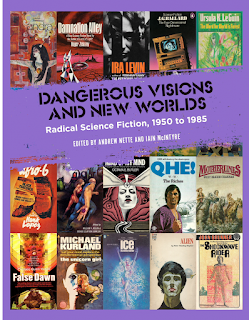

So it’s appropriate that these two publications would form the basis, and focal point, for a study of radical science fiction from 1950-1985. In fact, Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre, while keeping those publications firmly in mind, move both backwards and forwards in time with essays that extend the rebellious spirit, however varied, of New Worlds and Dangerous Visions. Nette and McIntyre’s volume really does cut a wide swathe, with excellently-researched essays from a variety of contributors on subjects that move across the board: from that utopias, dystopias, the bomb, revolution, the Vietnam war, race relations, feminism, the sexual revolution, ecology, and drugs, to sub-genres like Russian, gay, and young adult sci-fi, as well as chapters on publishers, editors, and writers, both obscure and well-known, from Moorcock, Judith Merril, Philip K. Dick, Samuel Delaney, Barry Malzberg, J.G. Ballard, Ursula LeGuin, Roger Zelazny, to Denis Jackson, Hank Lopez, R.A. Lafferty, Octavia Butler, and James Tiptree. With something for everyone, there are bound to be writers discussed that will be unfamiliar to readers. I for one had never come across the likes of Hank Lopez (Afro Six) or Denis Jackson ("Flying Saucers and Black Power"!). Likewise, there’s a plethora of paperback covers, all excellently reproduced which will make readers want to track down some of these titles on secondhand sites and bookstores.

In all, this is as complete a history of that period- 1950-1985- one is likely to come across. Though as I thumbed through its pages it did make me think about how so much of what considered radical during those years has now more or less become mainstream speculative fiction. But that probably says as much about how the genre has evolved as it does about this who now read the genre. If there is a criticism to make about the collection, it's that it doesn’t include contributions by the writers themselves. But then, in the end, this is essentially a book by sci-fi critics ands fans for other sci-if fans. Which it does in a format that has become something of a template for its editors. That is if their two collaborations- Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction 1950 to 1980, Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture 1950-1980- are anything to go by. All of which makes me wonder if Tex, minus the donkey jacket, is still around, and, if he is, if he's still reading what he once was so excited about. I hope so. Because, if nothing else, Dangerous Visions and New Worlds illustrates that it wasn’t, as the editors attest, so much a “long 1960s,” as a perpetual 1960s, however much those years and what they stood for have been, and continue to undergo such revision.

No comments:

Post a Comment