That Goldsmith, born in New York in 1913, would adapt his own novel was somewhat unusual in Hollywood at that time. What's interesting, however, is the degree to which the novel and screenplay differ, which they do in various, but interesting, ways. The most obvious difference is that the film is taken from the viewpoint of pianist Al Roberts who travels from the east coast to Hollywood to find and hopefully marry his girlfriend, Sue Harvey. While the novel, first published in 1939, is written from the dual perspective of violinist Alexander Roth (no doubt thought to be too Jewish sounding a name for movie audiences of the day) and Sue. Their stories are told in alternating chapters, with neither having any idea what the other is experiencing, or, for that matter, knowing what the other is really like. In the film adaptation, Al might not understand what Vera, the woman he picks up on the road, is about, or get the full drift of Haskell's story, but in the novel no one comprehends anyone. While the novel is about the general condition of knowing anyone, the movie is more about power, at least so far as it centers on Al's relationship with Vera, and her attempts to use him to her own ends.

That being the case, no wonder Goldsmith- for a while Anthony Quinn's brother-in-law- and Ulmer dispose of Sue's entries, and so move her to margins of the narrative. After all, it simplifies the story, turning it into a straight-ahead narrative, which no doubt made it easier and cheaper to film. All important factors for a Poverty Row enterprise to consider. But, in the end, no matter how cynical and hard-edged the film turned out, it pales in comparison to the novel.

Another difference between the novel and the film is that the latter leaves out an essential element of the former, namely Goldsmith's scathing critique of Hollywood, and the way it contributes to what Guy Debord would some years later call the society of the spectacle and where women are treated like objects- and, to quote the Dude, "objects are treated like women." Because it's Sue who mostly articulates that critique. Though, in the novel, Alex also has some choice words about Hollywood, little, if any, of which never quite made it onto the screen:

"You know, it would be a great thing if our lives could be arranged like a movie plot. M.G.M. does a much better job of running humanity than God. On the screen the good people always come out all right in the end...Things are plotted in straight lines. There are never any unexpected happenings which change everything about the hero but his underwear."

Still, had Ulmer and Goldsmith included the critique of Hollywood it no doubt would have resulted in an entirely different film, one that perhaps only a major studio could handle properly. Though perhaps hard to believe, but the novel is, if anything, even darker than the film, particularly regarding one of noir's traditional tropes, the part fate plays in a person's life. Speaking like an American Camus, Alex at one point says,

Still, had Ulmer and Goldsmith included the critique of Hollywood it no doubt would have resulted in an entirely different film, one that perhaps only a major studio could handle properly. Though perhaps hard to believe, but the novel is, if anything, even darker than the film, particularly regarding one of noir's traditional tropes, the part fate plays in a person's life. Speaking like an American Camus, Alex at one point says,"Here I had just sniffed out a human life as easily as falling off a log and the world was going on the same as always. The sun was still shining, the birds singing, the people eating, sleeping, working, making love, spanking their children, patting their dogs. It was undeniable proof that man is unimportant in the scheme of things, that one life more or less doesn't make a hell of a difference."

At the same time, the film does contain nuggets like, "Whichever way you turn. Fate sticks out a foot to trip you." Interestingly, the book ends with Alex pondering what might have happened had the car not stopped for him, saying, "God or Fate or some mysterious force can put the finger on you or on me for no good reason at all," the film ends with pretty much the same lines, but without any mention of God. After all, why confuse matters. Noir is noir. No point in needlessly throwing God into the mix.

While writing the above I was reminded of an article on Martin Goldsmith that appeared in Noir City, entitled The Vagabond by the excellent fiction writer and critic Jake Hinkson. He begins that piece with a quote by Columbia's president and chief of production Harry Cohn who purportedly said to Goldsmith, "You are the most dangerous man I have ever met because you have nothing to lose." If true, that says a lot about Goldsmith and who he was, as well as the demands made by Hollywood on most screenwriters at the time. In fact, Hinkson goes on to not only paint a picture of Goldsmith as something of a Hollywood existentialist, not only a perpetual outsider, who would periodically decamp in Hollywood to write for the studios- invariably a Poverty Row studio- and, money in hand, hit the road, not unlike Alex in Detour, in search of more salubrious surroundings. To back that up, Hinkson cities Goldsmith as saying, "You can live in comfort anywhere if you just revise your ideas of comfort... I think the ideal combination for making a man entirely independent would be a sleeping bag, a typewriter, a station wagon, and a telescope for stargazing."

|

| Goldsmith wearing sun glasses fasting in protest to school segregation, Los Angeles, 1964. |

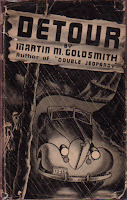

by the Nazis. While The Miraculous Fish of Domingo Gonzalez is a comic novel, perhaps in the B. Traven tradition, about a sleep Mexican fishing village where only sharks are caught. Until an American buyer of shark livers moves in changing the village beyond recognition. Goldsmith would go on to write for TV, with scripts for The Twilight Zone, Gunsmoke, Playhouse 90, and, in 1977, had a play produced by the Labor Theater in New York. Always politically active, Goldsmith joined the Congress of Racial Equality in the 1960s, and protested school segregation in Los Angeles. He also actively campaigned against nuclear weapons. He died in 1994, largely unheralded. I've heard rumours of an unpublished autobiography floating around, which would no doubt make for fascinating reading. Certainly anyone who appreciates Detour the film should have a look Detour the novel. It's not all that difficult to come by, having, over the past few years, been reprinted by a various outfits. Who knows, maybe the time is right for some larger company to take punt on it. After all, if Black Wings Has My Angel can be reprinted by NYRB, then why not Detour? In the meantime, take your pick of various editions (my preference would be for the one with the Larry Block forward). And thumb a ride on that desert highway, whether to hell or Hollywood.

No comments:

Post a Comment