As the opening pages of Lloyd Bradley's book attest, black music has long been a mainstay of British culture, no more so than in the capital itself. West Indians, Africans and exiled black Americans, have for many years been making what has become the soundtrack to the city, often in cross-cultural circumstances. When I arrived in the early 1970s, ska, American soul, South African jazz (the Blue Notes, Brotherhood of Sound), then reggae and West African-based music were the sounds I heard. But black music, as Bradley points out, is constantly evolving, with some forms falling out of fashion, often caused by the dictates of the market, for instance the creation and perpetuation of the term "world music," or political factors, such as the demise of the Greater London Council, which promoted black music as part of their inclusive policies.

As the author of Bass Culture, Bradley is well-positioned to explore this vast subject. It's not a bad attempt, though it has some drawbacks. For one thing, to do justice to the subject would take a book twice as long. I suppose that's part of the problem. Bradley, who attempts to cover the music from sometime around 1919 to the present, breezes through the early years, name-checking the likes of jazzers and calypsonians like "Snakehips" Johnson, Rudolph Dunbar, Freddy Grant, Sam Manning, all of whom were heard in the capital long before the great Lord Kitchener arrived on the SS Windrush. Moreover, I would maintain that the first couple chapters, like the rest of the book, alongside recordings of the music under discussion, in this case CD anthologies like Topic Records' Black British Jazz, or Honest Jon's various volumes of London Is the Place For Me. For a more detailed account of the African diaspora's contribution to early British jazz, one could do worse than have a look at Andy Simon's lengthy on-line account,

Black British Swing, published in 2012.

In any case, Bradley, emphasising the relationship between history and the music, relies on some fairly solid informants. In the first two chapters, it's the legendary pianist Russell Henderson and his 1950s cohort, the steel pan virtuoso Sterling Betancourt. It's the informants that allow Bradley to delve into the music, the record labels and distributors active during the 1950s. The third chapter centres on South African jazz and is built around interviews with drummer Louis Moholo, Hazel Miller (wife of bassist Harry Miller) and formidable musician and composer Mike Westbrook. Here Bradley outlines the impact that the Blue Notes/Brotherhood of Breath had on the London music scene in the mid-1960s. The fourth chapter covers West African music in the capital, from Ambrose Campbell to Osibisa, from the viewpoint of Osibisa leader Teddy Osei, highlighting th importance of Sterns from its origins as an electrical supply shop to major record store and label, as well as the African Centre in Covent Garden, which became a popular venue for West African music. The fifth chapter, entitled Bass Lines, Brass Sections and All Things Equals, includes interviews with the visionary Eddy Grant, who, amongst other things, fronted the 1970s group, The Equals, and maintained a recording studio in Stamford Hill, as well as the the veteran singer from Carriacou, Root Jackson, who achieved cult status in the 1970s with the funk/soul outfit FBI, and who still can be heard gigging around London. But it's the following chapter on the creation and success of Lover's Rock- The Whole World Loves a Lovers- that I found the most interesting. Lovers Rock was never a genre that appealed to me when it appeared in the 1970s. However, it was not only a London phenomenon but, according to Bradley, a reaction to hardcore roots reggae, which tended to marginalise young West Indian women. What began in London soon became popular in Jamaica. In examining the cultural importance of Lovers Rock, Bradley touches on the roots of London reggae, the record labels, distributors, producers, sound systems and DJs. For this he relies on the renown bassist, producer and mix master Dennis Bovell, who recalls that competitions would be held, with the winner recording a single (without pay). It served the purpose getting young women back onto the dance floor and created enough product for Bovell's company to be taken seriously.

Unfortunately, for me, Bradley's book becomes less interesting from this point on, with chapters on BritFunk, recent sound systems, pirate stations and music in the digital age. Yet I still learned a lot from these chapters. Call me naive, but I had no idea that during the 1980s clubs had a quota for blacks at the door, even when black bands were playing. In the end, the book points out that black music has been a music of migrants, one that mixes countries of origin and musical styles with relative abandon. For instance, someone like Ambrose Campbell could move from jazz to calypso to West African music. Likewise, Teddy Osei. To this day London black music, though no longer the province of migrants as such, remains cross-racial, rebellious, and often cutting-edge.

However, there are problems with the book. For instance, someone should have told the author that most readers don't really care what football club he supports, that it has nothing to do with the book's subject matter. He also has an annoying habit of referring to interviewees by their first name even though it's sometimes been pages since he's last quoted them. Then there are self-conscious asides (no point in mentioning you are not related to someone simply you share a surname) and a deadline journalism style that does the subject no favours. Minor criticisms, but a good editor should have been on top of that kind of thing. Though the most humorous, if not ludicrous, example of editorial slackness crops up when Bradley attempts to name-check Airto Moreira, whose name comes out in the text as Ayrton Moreira- clearly a spellcheck chapeau to Peter Ayrton, the senior editor and founder of the book's publisher, Serpent's Tail.

And maybe my memory is faulty, but I'm sure Bradley gets it slightly wrong when talking about record shops in the 1970s and early 1980s. Dobells on Charing Cross Road closed in 1980, but Bradley seems to be saying that it existed concurrently with Ray's on Shaftsbury Avenue, which wasn't the case. Though he could have been referring to an earlier period when Ray's was Collet's on New Oxford Street, then Charing Cross Road. And why no mention of Honest Jon's, whose Soho shop specialised in reggae, or the shop in Camden Town where could always flip through a rack of very cheap African records. And what about Daddy Cool in Soho? Also, the book could have been improved by including a list of recordings, if only to make it easier for the reader to track down and listen to the music mentioned in the text. And what about a map so those unfamiliar with London could get a sense of how the music scene over the years shifted around the capital? In the end, with a little more research, more attention to detail- the opening chapter deserves a book on its own- and a more attentive editor, this could have been a much better book. While the definitive book on black music in London has yet to be written, Sounds Like London will do for starters.

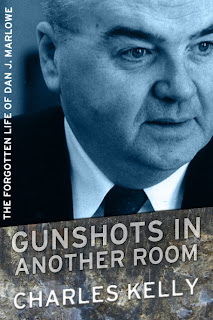

When compiling the list of favourite crime novels of 2013 there were some glaring omissions. No mention, for instance, of the latest by George Pelecanos, Walter Mosley, Scott Phillips or Reed Farrel Coleman. My reason for not including a number of books was simple enough: I not yet read them (blame the publishers for not sending copies). Also, no mention of Jean-Claude Izzo's magnificent Marseilles Trilogy- Total Chaos, Chourmo and Solea- probably because I'd read all three years ago. And no Gone Girl. But wasn't that one published in 2012? On the other hand, it was a list of my favourite books, not a list of the best books of 2013.

When compiling the list of favourite crime novels of 2013 there were some glaring omissions. No mention, for instance, of the latest by George Pelecanos, Walter Mosley, Scott Phillips or Reed Farrel Coleman. My reason for not including a number of books was simple enough: I not yet read them (blame the publishers for not sending copies). Also, no mention of Jean-Claude Izzo's magnificent Marseilles Trilogy- Total Chaos, Chourmo and Solea- probably because I'd read all three years ago. And no Gone Girl. But wasn't that one published in 2012? On the other hand, it was a list of my favourite books, not a list of the best books of 2013.