It seems the truth, if this is the truth- and I've no reason to think it's not- about JFK's assassination goes far beyond the noir musings of novelists like Ellroy and DeLillo. In fact, Douglass' book is probably as noir as true crime gets. I have to admit, I've never been one to declaim JFK as a man of peace. Nor did I believe he was on the verge of withdrawing from Vietnam. At the same time, I've always considered the assassination a watershed in American culture. It was also an essential element in the creation of neo-noir fiction that appeared during and in the aftermath of the Vietnam war (which I discuss in my books Pulp Culture and Neon Noir). At the very least it helped promote the nation's obsession with conspiracies regarding the government, and the national security state. But Douglass' book prompted me, albeit some six years after its publication, to reassess JFK's assassination and the circumstances surrounding it.

Even though I'd never considered Oswald the lone shooter, but most likely part of a right-wing conspiracy involving the CIA and organised crime, I had no idea the extent of that conspiracy and subsequent cover-up, the reasons behind it, or JFK's evolving post-missile crisis politics. This even though I'd once been an avid reader of JFK assassination books by the likes of Mark Lane and Jim Garrison. But the scrupulously documented JFK and the Unspeakable brings all that past research together, and much more, including further information regarding the national security state's attempt to maintain the cold war, invade Cuba, launch a preemptive strike against the USSR and prolong the war in Vietnam. Against that, Douglass maintains that JFK had decided to dismantle the CIA and, with his test ban treaty, work with Khrushchev to end the cold war. That being the case, Douglass, a Catholic theologian and peace activist, insists that Kennedy was a threat to the military industrial complex- which Eisenhower had warned about only a couple years earlier- the CIA- about which Truman, even though he created it, had reservations- and the continuation of the cold war. And so had to be taken out of the picture.

This was a conspiracy both complex and paper-thin instigated, according to Douglass, by the likes of CIA head Allen Dulles, veteran spook-poet James Jesus Angleton, and perhaps Henry Cabot Lodge, who came from a family bitterly opposed to the Kennedy's. Unfortunately, JFK made the mistake of appointing Lodge ambassador to Vietnam, only for Lodge to subvert every attempt JFK made to wind-down US presence in the region. Though LBJ refused to scapegoat the USSR for the assassination, which could have turned the cold war into a hot war, he did little to confront the military-industrial complex regarding the assassination, their cold war perspective, or the country's presence in southeast Asia. No hagiography, Douglass doesn't gloss over JFK's faults, but conducts a thorough investigation of the era and events culminating in the most famous cover-up in modern history which Douglass, quoting Thomas Merton, categorises as the Unspeakable- "the void that contradicts everything that is spoken even before the words are said.; the void that gets into the language of public and official declarations at the very moment when they are pronounced, and makes them ring dead with the hollowness of the abyss." If you're going to read one book on JFK's assassination, or, for that matter, one true crime book, this is the one you should go for.

Some miscellaneous afterthoughts:

- I was surprised at just how close the US was to a military coup during the Cuban missile crisis. However, it wouldn't be an overstatement to say that JFK's assassination was, in fact, a military coup. Unfortunately, LBJ never sought to question the national security state, the military industrial complex, or US presence in Vietnam. But, as Douglass points out, though LBJ belonged to a different party, he had always had a good working relationship with Lodge.

- In the less than three years JFK had to deal with the Bay of Pigs, the missile crisis, the Berlin Wall, Laos, Vietnam, and Indonesia, any of which, if mishandled, could easily have resulted in a nuclear war.

- While living in Mexico City in 1965, I was told by another American that Oswald had been seen at the Russian embassy in that city. If the likes of young Americans living in Mexico such as myself knew about his presence in the city, you can bet that CIA wanted such information disseminated, and so add to the evidence that Oswald had a pretext- his hatred of America- to kill the president. Of course, we now know there was more than one Oswald, that the real Oswald most likely never visited Mexico City.

- The post-assassination fear that the CIA controlled the government has been represented in various films (Manchurian Candidate, Parallax View, etc.), and any number of spy and crime novels. In many ways it's trope that has outlived its usefulness. Which doesn't mean it wasn't true, at least until the Church hearings, only that most accepted it as fact. But today's nemesis is Wall Street and global capitalism, linked as they are to the military-industrial complex, which has grown out of proportion thanks to America's particular brand of military Keynesianism. When it comes to those in control, it's hardly the CIA, but the oligarchs and plutocrats, while their War on Terror has curtailed the rights of those at home and abroad, turning the CIA into a surveillance and killing machine, sub-contracting more than ever. A scenario that goes far beyond what the national security state sought during JFK's time.

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Thursday, March 14, 2013

Neo-Pulp Pronzini

Though I glossed over it when writing Pulp Culture or Neon Noir, I've never really given Bill Pronzini's work the attention it obviously deserves. This even though he's been writing for over half a century, and remains so highly regarded. But unfortunately he's certainly not the only hardboiled writer I've never found the time to read sufficiently. And to be honest, it was really the evocative covers- particularly Femme- illustrated by Glen Orbik and designed by Gail Cross, that, in this instance, that renewed my interest. I know, Bo Didley aside, one isn't meant to judge a book by its cover and all that, but in this case I did and I have no regrets for having done so. Because Pronzini, with his Nameless Detective, has to be one of the finest practitioners of neo-noir fiction around. He's old school enough to recall the likes of Ross Macdonald and new school enough to be of interest to those who like their writers to comment on contemporary concerns. Moreover, the idea of a Nameless Detective, who by now has apparently appeared in more than thirty books, continues to be an intriguing and provocative notion. The detective as blank slate on which his criminal investigations can be written goes back to Chandler's Philip Marlowe and, before that, Paul Cain's The Fast One. His prose is to-the-point, clear and conversational. From Femme:

Though I glossed over it when writing Pulp Culture or Neon Noir, I've never really given Bill Pronzini's work the attention it obviously deserves. This even though he's been writing for over half a century, and remains so highly regarded. But unfortunately he's certainly not the only hardboiled writer I've never found the time to read sufficiently. And to be honest, it was really the evocative covers- particularly Femme- illustrated by Glen Orbik and designed by Gail Cross, that, in this instance, that renewed my interest. I know, Bo Didley aside, one isn't meant to judge a book by its cover and all that, but in this case I did and I have no regrets for having done so. Because Pronzini, with his Nameless Detective, has to be one of the finest practitioners of neo-noir fiction around. He's old school enough to recall the likes of Ross Macdonald and new school enough to be of interest to those who like their writers to comment on contemporary concerns. Moreover, the idea of a Nameless Detective, who by now has apparently appeared in more than thirty books, continues to be an intriguing and provocative notion. The detective as blank slate on which his criminal investigations can be written goes back to Chandler's Philip Marlowe and, before that, Paul Cain's The Fast One. His prose is to-the-point, clear and conversational. From Femme:In the dozen years I spent in law enforcement and the thirty years I've been a private investigator, I never once had the misfortune to cross paths with this type of seductress. Never expected to. Never thought much about the breed except when confronted with one in a film or the pages of a book or the pulp magazines I collect... [A] real femme fatale in classic mode? Not even close. If you'd told me one day I would, and that her brand of evil would be like nothing I could ever have imagined, I'd have laughed and said no way.

Both these books are essentially novellas, yet they carry the punch of novels. In fact, Kinsmen, about a far-right group in the Pacific Northwest, first appeared some twenty years ago, but remains timely in an era when racism continues to raise its ugly head. My advice: get both of them, and treat yourself to a writer who, over the years, has honed his literary chops to perfection, and, like his predecessor, Ross Macdonald, can write convincingly about individuals and the effect of violence as well as the dark side of the culture. Now to turn my attention to some of those other seventy novels he's written over the past fifty years...

Thursday, February 21, 2013

Catching Up- Max Allan Collins's Target Lancer and Bye Bye, Baby, Ariel S. Winter's Twenty-Year Death, Richard Lingeman's The Noir Forties

The books have been piling up, so I thought I'd better try to clear some of the backlog with a few quick reviews.

-Target Lancer and Bye Bye, Baby by Max Allan Collins (Forge): I've always had a soft spot for Collins. If nothing else, he's certainly one of the hardest working guys in crime fiction. But you do have to be prepared to suspend no small amount disbelief to fully appreciate his work. How, after all, could one protagonist know so many notable people and be at the nexus of so many historical moments? Still, his books are invariably interesting and his last couple Nathan Heller-- "p.i. to the stars"- novels are no exception. Think James Ellroy minus the warped personal obsessions and off-the-wall perspective, though that, of course, is what makes Ellroy so fascinating as well as occasionally unreadable. Nevertheless, the two writers inhabit more or less the same historical territory, which is why Collins has said that he doesn't read his fellow-fabulator of history. Certainly, Collins is the more readable and also the more prosaic. Not that his protagonists are without their quirks and obsessions. Target Lancer concerns a plot to kill JFK, in November, 1963, but in Chicago rather than Dallas, where, according to historical records Collins claims to have uncovered, another attempt on JFK's life was being planned. All the usual suspects are included here, and, of course, Nate Heller is in the thick of it. This is someone who, in the past, has not only worked for RFK and Hoffa, but knows Sam Giancana and Jack Ruby, as well as Sinatra and any number of other Hollywood personalities. As usual, Collins gives good history, with an ability to reduce it all to a human level. In a sense I preferred Collins' previous Heller novel, Bye Bye, Baby, about the death of Marilyn Monroe. Though both subjects have been written about ad nauseum, at least in the latter, Collins gives a few minor characters some space. Which is a good thing, particularly if, like me, you adhere to the Grover Lewis school of reportage, and believe it's the minor characters- drivers, butlers, care givers and takers- that a writer should concentrate on. Naturally, there's an element of voyeurism in Heller's relationship to Monroe. But, then, how could a novel about Monroe not be voyeuristic?

-Target Lancer and Bye Bye, Baby by Max Allan Collins (Forge): I've always had a soft spot for Collins. If nothing else, he's certainly one of the hardest working guys in crime fiction. But you do have to be prepared to suspend no small amount disbelief to fully appreciate his work. How, after all, could one protagonist know so many notable people and be at the nexus of so many historical moments? Still, his books are invariably interesting and his last couple Nathan Heller-- "p.i. to the stars"- novels are no exception. Think James Ellroy minus the warped personal obsessions and off-the-wall perspective, though that, of course, is what makes Ellroy so fascinating as well as occasionally unreadable. Nevertheless, the two writers inhabit more or less the same historical territory, which is why Collins has said that he doesn't read his fellow-fabulator of history. Certainly, Collins is the more readable and also the more prosaic. Not that his protagonists are without their quirks and obsessions. Target Lancer concerns a plot to kill JFK, in November, 1963, but in Chicago rather than Dallas, where, according to historical records Collins claims to have uncovered, another attempt on JFK's life was being planned. All the usual suspects are included here, and, of course, Nate Heller is in the thick of it. This is someone who, in the past, has not only worked for RFK and Hoffa, but knows Sam Giancana and Jack Ruby, as well as Sinatra and any number of other Hollywood personalities. As usual, Collins gives good history, with an ability to reduce it all to a human level. In a sense I preferred Collins' previous Heller novel, Bye Bye, Baby, about the death of Marilyn Monroe. Though both subjects have been written about ad nauseum, at least in the latter, Collins gives a few minor characters some space. Which is a good thing, particularly if, like me, you adhere to the Grover Lewis school of reportage, and believe it's the minor characters- drivers, butlers, care givers and takers- that a writer should concentrate on. Naturally, there's an element of voyeurism in Heller's relationship to Monroe. But, then, how could a novel about Monroe not be voyeuristic? -The Twenty-Year Plan by Ariel S. Winter (Hard Case Crime): In fact, three novels, a triptych of sorts, that span twenty years. Each taking place in a different era and an homage to a specific hardboiled writer. The first, Malniveau Prison, set in France, pays its respects to Simenon, and effectively evokes the enclosed provinciality and contemplative voice of that author's Maigret novels, with a touch of his non-Maigret work thrown in for good measure. A corpse is uncovered, thought to come from an escape-proof prison where Inspector Pelleter has just been interviewing a serial killer. Later Pelleter comes across the murdered man's daughter, Clothilde, a teenager married to Shem, a wealthy American. The bodies of other prisoners are discovered, while Pelleter's interviews with the serial killer gives him a unique perspective on a series of grisly crimes. The second part, The Falling Star, is an homage to Chandler. Fortunately, Winter avoids imitating Chandler's eloquent but bitter style, which has been parodied all-too-often. At the same time, he manages to capture the moral dilemmas and anxieties of Chandler's protagonist. It's the 1940s and Chloe, a French movie actress,is being stalked, which prompts the head of security at her Hollywood studio to ask investigator Dennis Foster to look into the matter. Chloe is, of course, Clothilde, who by now has relocated to America with her husband. The latter is having an affair with a would-be actress who herself is later murdered. Foster believes it's a set-up. But the further he takes his investigation, the more he finds a Hollywood that's seething in corruption, ugliness and death. While his efforts reach a conclusion, Chloe winds up in a sanitarium. Which leads to the the third section, Police at the Funeral, which is an homage to Jim Thompson and the pulp tradition of the 1950s. Shem, now an alcoholic, is traveling back to attend the funeral of his first wife from whom he hopes to inherit enough money keep Chloe in her sanitarium. A first-person tale of someone whose drinking drives him into a nightmare world of violence, Shem does what any encrazed Thompson character might do: he accidentally commits a murder, tries to write a play, and gets conned by his current girlfriend. In a voice reminiscent of a Thompson protagonist, Shem says, "Killing someone was a whole lot like writing." In all, Winter's novel is a slow death as much about mood as plot, perceptive in its association of each era with a particular crime narrative.

-The Twenty-Year Plan by Ariel S. Winter (Hard Case Crime): In fact, three novels, a triptych of sorts, that span twenty years. Each taking place in a different era and an homage to a specific hardboiled writer. The first, Malniveau Prison, set in France, pays its respects to Simenon, and effectively evokes the enclosed provinciality and contemplative voice of that author's Maigret novels, with a touch of his non-Maigret work thrown in for good measure. A corpse is uncovered, thought to come from an escape-proof prison where Inspector Pelleter has just been interviewing a serial killer. Later Pelleter comes across the murdered man's daughter, Clothilde, a teenager married to Shem, a wealthy American. The bodies of other prisoners are discovered, while Pelleter's interviews with the serial killer gives him a unique perspective on a series of grisly crimes. The second part, The Falling Star, is an homage to Chandler. Fortunately, Winter avoids imitating Chandler's eloquent but bitter style, which has been parodied all-too-often. At the same time, he manages to capture the moral dilemmas and anxieties of Chandler's protagonist. It's the 1940s and Chloe, a French movie actress,is being stalked, which prompts the head of security at her Hollywood studio to ask investigator Dennis Foster to look into the matter. Chloe is, of course, Clothilde, who by now has relocated to America with her husband. The latter is having an affair with a would-be actress who herself is later murdered. Foster believes it's a set-up. But the further he takes his investigation, the more he finds a Hollywood that's seething in corruption, ugliness and death. While his efforts reach a conclusion, Chloe winds up in a sanitarium. Which leads to the the third section, Police at the Funeral, which is an homage to Jim Thompson and the pulp tradition of the 1950s. Shem, now an alcoholic, is traveling back to attend the funeral of his first wife from whom he hopes to inherit enough money keep Chloe in her sanitarium. A first-person tale of someone whose drinking drives him into a nightmare world of violence, Shem does what any encrazed Thompson character might do: he accidentally commits a murder, tries to write a play, and gets conned by his current girlfriend. In a voice reminiscent of a Thompson protagonist, Shem says, "Killing someone was a whole lot like writing." In all, Winter's novel is a slow death as much about mood as plot, perceptive in its association of each era with a particular crime narrative. -The Noir Forties- The American People from Victory to Cold War by Richard Lingeman (Nation Books): I only wish Lingeman had spent more time on the subject of noir and its relationship to the era from which it derived. After all, that's what the title suggests. However, Lingeman's more interested in the period itself, which he relates along with personal asides that more or less bookend his study. If not more noir, then perhaps a bit more of the personal stuff. Not that the history of that era, one that corresponds with the golden age of noir, isn't important or interesting. It's just one tends to get lost in the telling, and it's not as if some of it has not been told before. To be fair, the book is as much a history as a paean to the the struggle of liberals and progressives, and the effect and aftermath of the New Deal. And to his credit, Lingeman intersperses that history and struggle with individual stories and side-glances towards various art forms. Nevertheless, the book, or at least its title, only serves to remind me the degree to which the term "noir" has become co-opted, not so much in Lingeman's book as in the culture at large. To the point where the term refers simply to a particular style or look. In other words, noir, as a concept, has become depoliticised. Having said that, Lingeman can be interesting when talking about such films- at least he is in this interview for the Nation- and how regressive politics can sometimes lead to inventive and highly political films. He even quotes Borde and Chaumeton in their famous essay, saying, "In every sense of the word, a noir film is a film of death." About his undercover work in Japan during the Korean War, where his job was to keep tabs on Japanese ultra nationalists, Lingeman says, "Working in this shadow world, I developed a taste for the night city, with its louche back-alley bars and hot-bed hotels, the exhilarating dangers, the sense of living on the edge." I wanted to hear more about that as well, which sounds like it could have been a noir narrative in itself. So next time, more noir, please. Although one shouldn't be seduced by the title, Lingeman's book is fine for those who want their history with a small dose of noir. But if you're after a larger dose, backed by history, you'd be better advised to stick to the likes of Naremore's More Than Night and Christopher's Somewhere In the Night.

-The Noir Forties- The American People from Victory to Cold War by Richard Lingeman (Nation Books): I only wish Lingeman had spent more time on the subject of noir and its relationship to the era from which it derived. After all, that's what the title suggests. However, Lingeman's more interested in the period itself, which he relates along with personal asides that more or less bookend his study. If not more noir, then perhaps a bit more of the personal stuff. Not that the history of that era, one that corresponds with the golden age of noir, isn't important or interesting. It's just one tends to get lost in the telling, and it's not as if some of it has not been told before. To be fair, the book is as much a history as a paean to the the struggle of liberals and progressives, and the effect and aftermath of the New Deal. And to his credit, Lingeman intersperses that history and struggle with individual stories and side-glances towards various art forms. Nevertheless, the book, or at least its title, only serves to remind me the degree to which the term "noir" has become co-opted, not so much in Lingeman's book as in the culture at large. To the point where the term refers simply to a particular style or look. In other words, noir, as a concept, has become depoliticised. Having said that, Lingeman can be interesting when talking about such films- at least he is in this interview for the Nation- and how regressive politics can sometimes lead to inventive and highly political films. He even quotes Borde and Chaumeton in their famous essay, saying, "In every sense of the word, a noir film is a film of death." About his undercover work in Japan during the Korean War, where his job was to keep tabs on Japanese ultra nationalists, Lingeman says, "Working in this shadow world, I developed a taste for the night city, with its louche back-alley bars and hot-bed hotels, the exhilarating dangers, the sense of living on the edge." I wanted to hear more about that as well, which sounds like it could have been a noir narrative in itself. So next time, more noir, please. Although one shouldn't be seduced by the title, Lingeman's book is fine for those who want their history with a small dose of noir. But if you're after a larger dose, backed by history, you'd be better advised to stick to the likes of Naremore's More Than Night and Christopher's Somewhere In the Night.Friday, February 15, 2013

Gunshots In Another Room: The Forgotten Life of Dan J. Marlowe by Charles Kelly

If Charles Kelly's intimate portrait of the hardboiled writer, Dan J. Marlowe, Gunshots In Another Room isn't quite on a par with Polito on Thompson, Garnier on Goodis, Sallis on Himes and Freeman on Chandler, it isn't far off. And in a sense, all the more interesting because, unlike the above, Marlowe, to date, isn't as well known, and, for the most part, hasn't been given the credit he deserves.

Like Goodis and Thompson, Marlowe spent years churning out paperback originals for the likes of Gold Medal. A jobbing writer, his was a world of word-counts, a study of the writing market and how he might publish and profit from it. Willing to take on anything that presented itself, he published not only crime novels but spy stories, pornography, books for young adults, newspaper columns, reviews, etc.. Anything that enabled him to make a living from his typewriter. In 1968 he claimed to have written 894,000 commercial words, for which he made something in the region of $10,000.

My first exposure to Marlowe's was his classic The Name of the Game Is Death. It's a sleazy crime-on-the-road novel, with a tough-guy protagonist whose sexual identity is never less than ambiguous. A novel that Stephen called "the hardest of the hardboiled." So intrigued was I by Marlowe's novel that I immediately had to dig deeper not only into his writing but into the genre itself, which led to what must have been my first article on hardboiled fiction, Sleaze y Sleuth, which appeared in Rolling Stock, a periodical edited by Ed and Jenny Dorn back in the mid-1980s.

Until reading Kelly's well-researched book, I knew little about Marlowe. Now, amongst other things, I know he was a hard drinker and, despite his Archie Bunker appearance, something of a womaniser, with old-school manners and moderate Republican politics. And that he only turned to writing in his mid-forties, after working at various jobs, making money as a professional gambler and a stint as a minor politician. Like his protagonist in Name of the Game..., Marlowe moved around the country, settling in Florida, Michigan and, finally, Los Angeles. He claimed his first novel, Doorway to Death, was written with only a character in mind, but without a plot. And even though he was nothing like his protagonists, he did befriend a bank robber, Al Nussbaum, incorporating him into his fiction as well as living with, or near him, for much of his life. Likewise, a substantial portion of the book is devoted to Nussbaum's true crime exploits.

Until reading Kelly's well-researched book, I knew little about Marlowe. Now, amongst other things, I know he was a hard drinker and, despite his Archie Bunker appearance, something of a womaniser, with old-school manners and moderate Republican politics. And that he only turned to writing in his mid-forties, after working at various jobs, making money as a professional gambler and a stint as a minor politician. Like his protagonist in Name of the Game..., Marlowe moved around the country, settling in Florida, Michigan and, finally, Los Angeles. He claimed his first novel, Doorway to Death, was written with only a character in mind, but without a plot. And even though he was nothing like his protagonists, he did befriend a bank robber, Al Nussbaum, incorporating him into his fiction as well as living with, or near him, for much of his life. Likewise, a substantial portion of the book is devoted to Nussbaum's true crime exploits.

Marlowe, by his own admission, was putting in "more sixteen than eight hour days." Maybe that had something to do with his subsequent amnesia, accompanied by aphasia. The cause was never discovered, though Marlowe would claim they were the result of a stroke. It would take him years to put his life back together, having to relearn how to live and write. Kelly relates all this and more with a sharp and sympathetic eye and a hardboiled style. Informative and well-written, Gunshots In Another Room makes for quite a story.

Marlowe, by his own admission, was putting in "more sixteen than eight hour days." Maybe that had something to do with his subsequent amnesia, accompanied by aphasia. The cause was never discovered, though Marlowe would claim they were the result of a stroke. It would take him years to put his life back together, having to relearn how to live and write. Kelly relates all this and more with a sharp and sympathetic eye and a hardboiled style. Informative and well-written, Gunshots In Another Room makes for quite a story.

Like Goodis and Thompson, Marlowe spent years churning out paperback originals for the likes of Gold Medal. A jobbing writer, his was a world of word-counts, a study of the writing market and how he might publish and profit from it. Willing to take on anything that presented itself, he published not only crime novels but spy stories, pornography, books for young adults, newspaper columns, reviews, etc.. Anything that enabled him to make a living from his typewriter. In 1968 he claimed to have written 894,000 commercial words, for which he made something in the region of $10,000.

My first exposure to Marlowe's was his classic The Name of the Game Is Death. It's a sleazy crime-on-the-road novel, with a tough-guy protagonist whose sexual identity is never less than ambiguous. A novel that Stephen called "the hardest of the hardboiled." So intrigued was I by Marlowe's novel that I immediately had to dig deeper not only into his writing but into the genre itself, which led to what must have been my first article on hardboiled fiction, Sleaze y Sleuth, which appeared in Rolling Stock, a periodical edited by Ed and Jenny Dorn back in the mid-1980s.

Until reading Kelly's well-researched book, I knew little about Marlowe. Now, amongst other things, I know he was a hard drinker and, despite his Archie Bunker appearance, something of a womaniser, with old-school manners and moderate Republican politics. And that he only turned to writing in his mid-forties, after working at various jobs, making money as a professional gambler and a stint as a minor politician. Like his protagonist in Name of the Game..., Marlowe moved around the country, settling in Florida, Michigan and, finally, Los Angeles. He claimed his first novel, Doorway to Death, was written with only a character in mind, but without a plot. And even though he was nothing like his protagonists, he did befriend a bank robber, Al Nussbaum, incorporating him into his fiction as well as living with, or near him, for much of his life. Likewise, a substantial portion of the book is devoted to Nussbaum's true crime exploits.

Until reading Kelly's well-researched book, I knew little about Marlowe. Now, amongst other things, I know he was a hard drinker and, despite his Archie Bunker appearance, something of a womaniser, with old-school manners and moderate Republican politics. And that he only turned to writing in his mid-forties, after working at various jobs, making money as a professional gambler and a stint as a minor politician. Like his protagonist in Name of the Game..., Marlowe moved around the country, settling in Florida, Michigan and, finally, Los Angeles. He claimed his first novel, Doorway to Death, was written with only a character in mind, but without a plot. And even though he was nothing like his protagonists, he did befriend a bank robber, Al Nussbaum, incorporating him into his fiction as well as living with, or near him, for much of his life. Likewise, a substantial portion of the book is devoted to Nussbaum's true crime exploits.  Marlowe, by his own admission, was putting in "more sixteen than eight hour days." Maybe that had something to do with his subsequent amnesia, accompanied by aphasia. The cause was never discovered, though Marlowe would claim they were the result of a stroke. It would take him years to put his life back together, having to relearn how to live and write. Kelly relates all this and more with a sharp and sympathetic eye and a hardboiled style. Informative and well-written, Gunshots In Another Room makes for quite a story.

Marlowe, by his own admission, was putting in "more sixteen than eight hour days." Maybe that had something to do with his subsequent amnesia, accompanied by aphasia. The cause was never discovered, though Marlowe would claim they were the result of a stroke. It would take him years to put his life back together, having to relearn how to live and write. Kelly relates all this and more with a sharp and sympathetic eye and a hardboiled style. Informative and well-written, Gunshots In Another Room makes for quite a story. Sunday, January 27, 2013

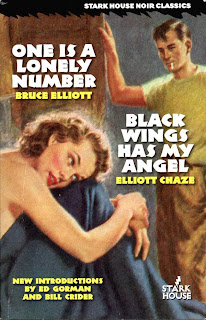

Black Wings Has My Angel by Elliott Chaze and One Is a Lonely Number by Bruce Elliott

Over the years Elliott Chaze's Black Wings Has My Angel has taken on a near-legendary status, and become one of the most sought-after of Gold Medal novels. It's title alone- poetic and darkly evocative- is enticing enough. True to form, Gold Medal's teaser for this 1953 paperback pitched it somewhere between the sublime and ridiculous: "She had the face of a madonna and a heart made of dollar bills." However, since then Black Wings... has also gained a reputation as the most literary of pulp novels. And, happily, Chaze's novel, as this wonderful Stark House reissue attests, easily lives up to its reputation.

A year after it was published in the US, it appeared on the Serie Noire imprint in France, albeit in the usual, for that publishing house, truncated form, with the title Il gele en enfer (roughly "Hell Freezes Over"). Back then Chaze was publishing stories in the New Yorker, Cosmopolitan and Colliers, and putting together a string of novels, though none would be as visceral or pulp-oriented as Black Wings...

Black Wings... is narrated in the first person by "Tim Sunblade," a recent escapee from Parchman Farm, who meets Virginia, a call-girl he's hired to satisfy his post-prison hunger. His ambition is to pull off a robbery that will set him up for life. Virginia is beautiful but highly unpredictable. She too has a past and is an escapee of sorts. At first Tim simply wants to get rid of her, but soon realizes she might be useful. Eventually he falls in love with her. Together they pull off the robbery, but that, of course, is just the beginning of their problems.

"I was sick of Virginia, too, and of what the money had done to the both of us, changing a tough, elegant adventuress with plenty of guts and imagination into a candy-tonguing country club Cleopatra who nested in bed the whole day long and thought her feet were too damned good to walk on."

Spending most of his time in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, Chaze also worked as an Associated Press reporter in Colorado and Louisiana. Not surprisingly, these three locales- Mississippi, Colorado and Louisiana- form the backdrop to Black Wings.... By the time Chaze died in Mamou, Louisiana in 1990, he only had a hint that his book had developed a cult following. The likes of Max Collins, Bill Prozini and Edward Gorman had proclaimed Black Wings... the quintessential Gold Medal novel, and Barry Gifford paid him a visit in Hattiesburg to talk about Black Lizard publishing his novel, writing about the experience and the book in an issue of Oxford American. Unfortunately, Gifford's plans had to be ditched when new owners took over his company. Presently, Black Wings... is about to hit the screen, starring Anna Paquin and Elija Wood, with a screenplay by Gifford. I hope it turns out to be at least half as good as the book, though, of course, I'm not betting on it.

"I couldn't stand not to look either. I think I'm going crazy. I've got to look at it and I can't, like a woman who's known for months she had a cancer and the doctor finally tells her it's there and he tells her where to look to see it. And she must look at it but she can't.”

Chaze's novel is preceded by another downbeat narrative, this one by Bruce Elliott entitled One is a Lonely Number. I hadn't had much intention of reading this one, but two pages into the book I was hooked and finished it off in two sittings. How could I not with paragraphs like this:

"The night was dark but alive. It was too hot to sleep in stinking box-like rooms, rooms just enough bigger than a coffin so that bodies had to be moved when they died, but not big enough so a human could endure living in them. Radios blared from the open windows all around him. Middle-aged blowsy women hung out windows, looking, searching, as if they could see something that would be different enough from what they had seen the night before so that later they could say, oh that musta been the night that Charley got cut up, or Betty got punched around, or whatever it was they were looking for, waiting for."

Not as literary as Black Wings..., but the writing is still very good, feeding into a rapid-fire narrative, which, by the end, will leave you gasping. And it's as perverse a tale as you're going to read, one that fits squarely in the Jim Thompson-Gil Brewer school of warped hard-boiled prose. The novel opens with Larry, an ex-musician, and yet another escapee from prison- in this case Joliet- in bed with a prostitute. All he needs to do is get some money together and get to Mexico. Needless to say, with everyone trying to get him to do their dirty work, his plans do not according to plan.

Not that much is known about Bruce Elliott. His real name was Walter Gardner Lively Syacy, was born in 1915, hit by a car in 1972 and ended up in a coma, before dying in 1973. One Is a Lonely Number was published in the US by Lion Books in 1952 and in France under the title Un tout seul in 1954. As well as mysteries, Elliott wrote sci-fi, including a comic fantasy about Satan entitled The Devil Was Sick, TV scripts and a number of stories for Shadow magazine. He was also a stage magician who wrote various books on the subject, including Professional Magic Made Easy and The Professional Magician. One Is a Lonely Number represents yet another lost novel unearthed by Stark House, which, as far as I'm concerned, has become one of the preeminent publishers of hardboiled fiction.

Friday, January 11, 2013

Notes on Robert C. Pippin's Fatalism in American Film Noir

Concise- some 130 pages, including notes- and surprisingly accessible, Fatalism in American Film Noir (University of Virginia Press) by the Hegelian University of Chicago professor Robert B. Pippin constitutes, perhaps for the first time, a philosopher's take on the genre. It centers in particular on agency, i.e., the extent to which film noir protagonists are agents of their own actions. It's true, noir protagonists exhibit a certain helplessness, as though their actions, or the motivation to act, derive from outside themselves, whether the result of fate, obsession or socioeconomic factors. Pippin cites Burt Lancaster in Criss Cross and The Killers as demonstrating this passive tendency, immobilized by his belief that he's been dealt a hand over which he has little, if any, control. Clearly, it's no coincidence that the question of agency, and film noir, came at particular moment in history. According to Pippin, these films show us "what it literally looks like, what it feels like, to live in a world where the experience of our own agency has begun to shift."

Fatalism... centers on three works: Jacques Tourneur's 1947 Out of the Past, Orson Welles' 1948 The Lady From Shanghai and Fritz Lang's 1945 Scarlet Street. Pippin points that in Out of the Past we are both shown events and, through flashbacks and a voice-over, we are told about those events. Consequently, there's a gap between what we see is happening and what the narrator, in explaining himself to Ann, maintains is happening. Yet the flashback is less a particular perspective on what is shown than another element of what is being shown, which, in itself, necessitates interpretation. It's as though Jeff, in his narration, is saying this is the way it happened, I can't change anything now, and I couldn't change anything then, making him both a spectator as well as an active participant in the narrative, and his narrative the sole means by which his agency can be recovered.

The fact is, Jeff is unable to move out of the past, in this case his relationship with femme fatale Kathie, believing- here Pippin quotes Oedipus- "I suffered those deeds more than I acted them." Of course, the likes of Jeff aren't thinkers, but improvisers who move from one event to another, trying to create a space for themselves in which to act, only to be stymied by their past. Like Chinatown, the narrative has to be renegotiated once the ending has been revealed and the protagonist's agency can come into focus. Trapped by what he does and who he is, Jeff seeks to become the agent of his actions, only to meet his death. It's as if, for Jeff, the beginning and end have already been written, and he's marking time, waiting for his time to run out. Any room for self-generated action is limited, though the heroic-existential position is to act despite everything. "He ends up an agent," says Pippin, "however restricted and compromised, in the only way one can be. He acts like one." And then he dies.

Like Jeff, Michael, the protagonist in Welles' The Lady From Shanghai, is apparently robbed of his free will by another femme fatale, in this case Rita Hayworth. Here Pippin is interested in how the femme fatale can affect a protagonist and his ability to act, to be rational, and to reflect on and understand his actions. Pippin points out that the femme fatale is often the mirror image of her relationship to the other man, not the one for whom they are fatal. In that other relationship, the woman is controlled, manipulated, threatened and financially dependent upon, to the point that, in that relationship, they too can do nothing on their own. Pippin goes on to say that Welles is here showing another type of femme fatale from the one Hayward portrayed in Gilda, cutting her hair, keeping her relatively static, and shooting her from close-range. In this film too the narrator is not exactly the same person in the film. Something has changed. For instance, Michael claims to be political, but, in the narration, he is anything but. So in the space between the showing and the telling something has happened, but the viewer doesn't know if that change has occurred in the film, a character development, or it has taken place in the novel Michael is purportedly writing. Pippin quotes the protagonist, saying, "I never make up my mind about anything until it's over and done with." Which becomes something of a slogan for the author, citing it again in the concluding chapter. In other words, it's important that Michael lives in the moment, because it's the process that matters. According to Pippin: "It's not that he is mindless; there are just many provisional possibilities. To be 'sure of what one intended' is to be sure of what one is committed to doing, and avowals of such intentions are therefore not reports of the already resolved; they are the resolve and are often provisional."

Like Jeff, Michael, the protagonist in Welles' The Lady From Shanghai, is apparently robbed of his free will by another femme fatale, in this case Rita Hayworth. Here Pippin is interested in how the femme fatale can affect a protagonist and his ability to act, to be rational, and to reflect on and understand his actions. Pippin points out that the femme fatale is often the mirror image of her relationship to the other man, not the one for whom they are fatal. In that other relationship, the woman is controlled, manipulated, threatened and financially dependent upon, to the point that, in that relationship, they too can do nothing on their own. Pippin goes on to say that Welles is here showing another type of femme fatale from the one Hayward portrayed in Gilda, cutting her hair, keeping her relatively static, and shooting her from close-range. In this film too the narrator is not exactly the same person in the film. Something has changed. For instance, Michael claims to be political, but, in the narration, he is anything but. So in the space between the showing and the telling something has happened, but the viewer doesn't know if that change has occurred in the film, a character development, or it has taken place in the novel Michael is purportedly writing. Pippin quotes the protagonist, saying, "I never make up my mind about anything until it's over and done with." Which becomes something of a slogan for the author, citing it again in the concluding chapter. In other words, it's important that Michael lives in the moment, because it's the process that matters. According to Pippin: "It's not that he is mindless; there are just many provisional possibilities. To be 'sure of what one intended' is to be sure of what one is committed to doing, and avowals of such intentions are therefore not reports of the already resolved; they are the resolve and are often provisional."

In Scarlet Street, Pippin discusses how Chris seeks to break out of his own self-inscribed world, even relating it to the film's final music, which morphs from a Christmas tune to Melancholy Baby- heard earlier, the needle stuck, like Chris's life- to Jingle Bells. It's as though Lang is counterposing the socioeconomic facts of Chris's life with the Christian version of fate and redemption. Of course, he also makes the not-all-that-astonishing observation that everyone in the film is trapped by their class, their culture, and their understanding of themselves, which narrows their future course of action. I had no choice is the usual excuse. But these characters are neither free nor fated. They make choices, even if they are trapped by them. Says Pippin, "The danger of exaggerating our capacity for self-initiated action and so exaggerating both a burden of responsibility and a way of avoiding a good deal of blame is...as great as the danger of throwing up our hands and in a self-undermining way becoming the all-pervasive power of fate." Film noir, then, is testimony to the limited space in which one can act freely, whatever the consequences. Pippin quotes McDowell from his book on Wittgenstein, Mind, Value and Reality: "One does not need to wait and see what one does before one can know what one intends."

In Scarlet Street, Pippin discusses how Chris seeks to break out of his own self-inscribed world, even relating it to the film's final music, which morphs from a Christmas tune to Melancholy Baby- heard earlier, the needle stuck, like Chris's life- to Jingle Bells. It's as though Lang is counterposing the socioeconomic facts of Chris's life with the Christian version of fate and redemption. Of course, he also makes the not-all-that-astonishing observation that everyone in the film is trapped by their class, their culture, and their understanding of themselves, which narrows their future course of action. I had no choice is the usual excuse. But these characters are neither free nor fated. They make choices, even if they are trapped by them. Says Pippin, "The danger of exaggerating our capacity for self-initiated action and so exaggerating both a burden of responsibility and a way of avoiding a good deal of blame is...as great as the danger of throwing up our hands and in a self-undermining way becoming the all-pervasive power of fate." Film noir, then, is testimony to the limited space in which one can act freely, whatever the consequences. Pippin quotes McDowell from his book on Wittgenstein, Mind, Value and Reality: "One does not need to wait and see what one does before one can know what one intends."

Fatalism... ends with a brief look at Double Indemnity, in which egoist/predator Phyllis conspires with easy-going nihilist Neff. But it's Keyes who, as arbiter, defines the boundaries separating accident, fate and intentionality. As a Socratic figure, Keyes doesn't condemn Neff, but recognizes that he's trapped, caught by fate. Since it's Keyes' job to realize such things, he, according to Pippin, must bear the burden of the narrative. Here, as in other films noirs, accident plays an important part, with the protagonist convinced he will be blamed by the police, so concludes that there's no reason why he shouldn't do what he is fated to be blamed for. In Double Indemnity. Phyllis suffers her fate because she finally acts as a free agent, not shooting Neff a second time, which leads to her death.

Interestingly, Pippin has also written a book on westerns, Hollywood Westerns and American Myth. In Fatalism... he discusses the various differences surrounding the two genres whose classic films emerged at approximately the same time. Of course, he points out that many westerns turn out to be simply film noir on horseback. But for the most part they stand in opposition to one another, particularly when it comes to the American dream, domestic life, the role of the protagonist, agency (possible in westerns), world view (Manichaean vs a more nuanced perspective), etc.. Likewise, visual style. Westerns, according to Pippin, are horizontal- broad vistas, distant horizons, a stationary camera, daylight, etc.- while noir tends to be visually vertical- stairs, bars, shadows of blinds or bars, elevators, tight shots, unreliable narrator, night, disorientating camera, etc..

Interestingly, Pippin has also written a book on westerns, Hollywood Westerns and American Myth. In Fatalism... he discusses the various differences surrounding the two genres whose classic films emerged at approximately the same time. Of course, he points out that many westerns turn out to be simply film noir on horseback. But for the most part they stand in opposition to one another, particularly when it comes to the American dream, domestic life, the role of the protagonist, agency (possible in westerns), world view (Manichaean vs a more nuanced perspective), etc.. Likewise, visual style. Westerns, according to Pippin, are horizontal- broad vistas, distant horizons, a stationary camera, daylight, etc.- while noir tends to be visually vertical- stairs, bars, shadows of blinds or bars, elevators, tight shots, unreliable narrator, night, disorientating camera, etc..

There's something heartening reading someone who believes shared knowledge might ultimately lead to self-knowledge, and that ethics matter whether we are free agents or not. Despite its size, Pippin's book gives the reader a lot to think about. Few are going to agree with everything he says. For instance, he talks about urbanization as a contributing factor to film noir. For me that's a slight over-simplification. It's not just urbanization, but the anxiety of urbanization, and the flight to the suburbs, illustrated by the likes of Lang's The Big Heat or De Toth's The Pitfall. Nevertheless, Pippin's book made me think about these films in a fresh way. For me, that's saying a lot.

Fatalism... centers on three works: Jacques Tourneur's 1947 Out of the Past, Orson Welles' 1948 The Lady From Shanghai and Fritz Lang's 1945 Scarlet Street. Pippin points that in Out of the Past we are both shown events and, through flashbacks and a voice-over, we are told about those events. Consequently, there's a gap between what we see is happening and what the narrator, in explaining himself to Ann, maintains is happening. Yet the flashback is less a particular perspective on what is shown than another element of what is being shown, which, in itself, necessitates interpretation. It's as though Jeff, in his narration, is saying this is the way it happened, I can't change anything now, and I couldn't change anything then, making him both a spectator as well as an active participant in the narrative, and his narrative the sole means by which his agency can be recovered.

The fact is, Jeff is unable to move out of the past, in this case his relationship with femme fatale Kathie, believing- here Pippin quotes Oedipus- "I suffered those deeds more than I acted them." Of course, the likes of Jeff aren't thinkers, but improvisers who move from one event to another, trying to create a space for themselves in which to act, only to be stymied by their past. Like Chinatown, the narrative has to be renegotiated once the ending has been revealed and the protagonist's agency can come into focus. Trapped by what he does and who he is, Jeff seeks to become the agent of his actions, only to meet his death. It's as if, for Jeff, the beginning and end have already been written, and he's marking time, waiting for his time to run out. Any room for self-generated action is limited, though the heroic-existential position is to act despite everything. "He ends up an agent," says Pippin, "however restricted and compromised, in the only way one can be. He acts like one." And then he dies.

Like Jeff, Michael, the protagonist in Welles' The Lady From Shanghai, is apparently robbed of his free will by another femme fatale, in this case Rita Hayworth. Here Pippin is interested in how the femme fatale can affect a protagonist and his ability to act, to be rational, and to reflect on and understand his actions. Pippin points out that the femme fatale is often the mirror image of her relationship to the other man, not the one for whom they are fatal. In that other relationship, the woman is controlled, manipulated, threatened and financially dependent upon, to the point that, in that relationship, they too can do nothing on their own. Pippin goes on to say that Welles is here showing another type of femme fatale from the one Hayward portrayed in Gilda, cutting her hair, keeping her relatively static, and shooting her from close-range. In this film too the narrator is not exactly the same person in the film. Something has changed. For instance, Michael claims to be political, but, in the narration, he is anything but. So in the space between the showing and the telling something has happened, but the viewer doesn't know if that change has occurred in the film, a character development, or it has taken place in the novel Michael is purportedly writing. Pippin quotes the protagonist, saying, "I never make up my mind about anything until it's over and done with." Which becomes something of a slogan for the author, citing it again in the concluding chapter. In other words, it's important that Michael lives in the moment, because it's the process that matters. According to Pippin: "It's not that he is mindless; there are just many provisional possibilities. To be 'sure of what one intended' is to be sure of what one is committed to doing, and avowals of such intentions are therefore not reports of the already resolved; they are the resolve and are often provisional."

Like Jeff, Michael, the protagonist in Welles' The Lady From Shanghai, is apparently robbed of his free will by another femme fatale, in this case Rita Hayworth. Here Pippin is interested in how the femme fatale can affect a protagonist and his ability to act, to be rational, and to reflect on and understand his actions. Pippin points out that the femme fatale is often the mirror image of her relationship to the other man, not the one for whom they are fatal. In that other relationship, the woman is controlled, manipulated, threatened and financially dependent upon, to the point that, in that relationship, they too can do nothing on their own. Pippin goes on to say that Welles is here showing another type of femme fatale from the one Hayward portrayed in Gilda, cutting her hair, keeping her relatively static, and shooting her from close-range. In this film too the narrator is not exactly the same person in the film. Something has changed. For instance, Michael claims to be political, but, in the narration, he is anything but. So in the space between the showing and the telling something has happened, but the viewer doesn't know if that change has occurred in the film, a character development, or it has taken place in the novel Michael is purportedly writing. Pippin quotes the protagonist, saying, "I never make up my mind about anything until it's over and done with." Which becomes something of a slogan for the author, citing it again in the concluding chapter. In other words, it's important that Michael lives in the moment, because it's the process that matters. According to Pippin: "It's not that he is mindless; there are just many provisional possibilities. To be 'sure of what one intended' is to be sure of what one is committed to doing, and avowals of such intentions are therefore not reports of the already resolved; they are the resolve and are often provisional." In Scarlet Street, Pippin discusses how Chris seeks to break out of his own self-inscribed world, even relating it to the film's final music, which morphs from a Christmas tune to Melancholy Baby- heard earlier, the needle stuck, like Chris's life- to Jingle Bells. It's as though Lang is counterposing the socioeconomic facts of Chris's life with the Christian version of fate and redemption. Of course, he also makes the not-all-that-astonishing observation that everyone in the film is trapped by their class, their culture, and their understanding of themselves, which narrows their future course of action. I had no choice is the usual excuse. But these characters are neither free nor fated. They make choices, even if they are trapped by them. Says Pippin, "The danger of exaggerating our capacity for self-initiated action and so exaggerating both a burden of responsibility and a way of avoiding a good deal of blame is...as great as the danger of throwing up our hands and in a self-undermining way becoming the all-pervasive power of fate." Film noir, then, is testimony to the limited space in which one can act freely, whatever the consequences. Pippin quotes McDowell from his book on Wittgenstein, Mind, Value and Reality: "One does not need to wait and see what one does before one can know what one intends."

In Scarlet Street, Pippin discusses how Chris seeks to break out of his own self-inscribed world, even relating it to the film's final music, which morphs from a Christmas tune to Melancholy Baby- heard earlier, the needle stuck, like Chris's life- to Jingle Bells. It's as though Lang is counterposing the socioeconomic facts of Chris's life with the Christian version of fate and redemption. Of course, he also makes the not-all-that-astonishing observation that everyone in the film is trapped by their class, their culture, and their understanding of themselves, which narrows their future course of action. I had no choice is the usual excuse. But these characters are neither free nor fated. They make choices, even if they are trapped by them. Says Pippin, "The danger of exaggerating our capacity for self-initiated action and so exaggerating both a burden of responsibility and a way of avoiding a good deal of blame is...as great as the danger of throwing up our hands and in a self-undermining way becoming the all-pervasive power of fate." Film noir, then, is testimony to the limited space in which one can act freely, whatever the consequences. Pippin quotes McDowell from his book on Wittgenstein, Mind, Value and Reality: "One does not need to wait and see what one does before one can know what one intends."Fatalism... ends with a brief look at Double Indemnity, in which egoist/predator Phyllis conspires with easy-going nihilist Neff. But it's Keyes who, as arbiter, defines the boundaries separating accident, fate and intentionality. As a Socratic figure, Keyes doesn't condemn Neff, but recognizes that he's trapped, caught by fate. Since it's Keyes' job to realize such things, he, according to Pippin, must bear the burden of the narrative. Here, as in other films noirs, accident plays an important part, with the protagonist convinced he will be blamed by the police, so concludes that there's no reason why he shouldn't do what he is fated to be blamed for. In Double Indemnity. Phyllis suffers her fate because she finally acts as a free agent, not shooting Neff a second time, which leads to her death.

Interestingly, Pippin has also written a book on westerns, Hollywood Westerns and American Myth. In Fatalism... he discusses the various differences surrounding the two genres whose classic films emerged at approximately the same time. Of course, he points out that many westerns turn out to be simply film noir on horseback. But for the most part they stand in opposition to one another, particularly when it comes to the American dream, domestic life, the role of the protagonist, agency (possible in westerns), world view (Manichaean vs a more nuanced perspective), etc.. Likewise, visual style. Westerns, according to Pippin, are horizontal- broad vistas, distant horizons, a stationary camera, daylight, etc.- while noir tends to be visually vertical- stairs, bars, shadows of blinds or bars, elevators, tight shots, unreliable narrator, night, disorientating camera, etc..

Interestingly, Pippin has also written a book on westerns, Hollywood Westerns and American Myth. In Fatalism... he discusses the various differences surrounding the two genres whose classic films emerged at approximately the same time. Of course, he points out that many westerns turn out to be simply film noir on horseback. But for the most part they stand in opposition to one another, particularly when it comes to the American dream, domestic life, the role of the protagonist, agency (possible in westerns), world view (Manichaean vs a more nuanced perspective), etc.. Likewise, visual style. Westerns, according to Pippin, are horizontal- broad vistas, distant horizons, a stationary camera, daylight, etc.- while noir tends to be visually vertical- stairs, bars, shadows of blinds or bars, elevators, tight shots, unreliable narrator, night, disorientating camera, etc..

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)