Way back when, before I began reading Ross Macdonald, I was already well into Paul Nelson's writing, mainly through his and Jon Pancake's folk music magazine, Little Sandy Review. I was probably one of all of 200 subscribers. At that time, the magazine was, for me, the arbiter of taste in early 1960s folk America. Nelson's reviews were both conversational and erudite, as likely to cite Bergman, Truffaut and J.P. Donlevy as Uncle Dave Macon. It took Nelson a couple years to get to grips with his contemporary and fellow-Dinky Town contemporary Bob Dylan. Probably because it was hard for Nelson to move beyond traditional types, and dedicated disciples like the New Lost City Ramblers. But when he fell for Dylan, he fell hard. I remember in particular Nelson discussing the cinematic imagery in Dylan's The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll.

A few after my foray into the realm of Little Sandy, I crossed the rubicon and begin a long descent into the world of Ross Macdonald. It was Macdonald, along with Hammett and Himes who would be my introduction to hardboiled noir fiction. Which is to say, corruption in high places, accompanied by the poetry of street-level circumlocutions. To this day I still can't tell one Macondald novel from another. They really are all one novel, all one investigation and, as in the title of Kevin Avery and Jeff Wong's book, all one case. Which is say, they are all about the culture and its discontent, particularly when it comes to families, and how, as the man said, they really do fuck you up.

I stopped gumshoeing Nelson in the 70s, though I remember reading some of his rock criticism in Rolling Stone and elsewhere, always finding it interesting and eclectic. Because for him, as for Macdonald, it was also all one case- fiction, film writing, westerns, noir, music. Whether Gatsby, John Ford, Hammett or Warren Zevon, it was all part of the same American landscape. But instead of using his multiple interests and talents to take him to new heights, Nelson would apparently find the combinations so overwhelming and intense that they would eventually silence him. Or maybe he'd said it all, was unable to say anymore. Or it could simply be that he could not edit himself any longer or make it all cohere. Capable of so much, Nelson would end up delivering much less than he could have. Even so what he did manage to produce was always interesting and often brilliant, whether zooming-in for close-ups of his favorite musicians or writers, or panning-out for wide shots of the culture in general. Unfortunately, he could never get it together to write that elusive novel or film, until it all went silent and he ended his days as a reclusive clerk in a video store. Not so different from the way a young Quentin Tarantino began his career. And there is a little bit of Nelson in Tarantino. As for Macdonald, I would over the years revisit his work, occasionally picking up one of his novels only to marvel at his writing, the depths he was able to reach, all of which reminded me that this was why I got interested in this type of writing, because it's capable of saying so much. Of course must have felt much the same way.

Kevin Avery's biography of Nelson expanded on the information I had previously gleaned from Nolan's biography of Macdonald, namely that Nelson had conducted a marathon interview with Macdonald, pitching up his tent in Macdonald's house for some weeks. I remember writing to Kevin saying, just as so many others had, something along the lines of

what, there's hundreds of hours of interviews Nelson did with Macdonald. Shouldn't they be made available. He assured me that they soon would be.

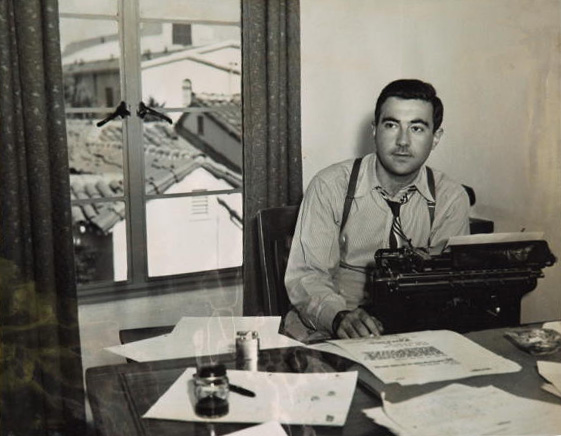

But I had no idea the material would be presented so exquisitely, thanks largely to graphic designer Jeff Wong. In fact, with the exception of photos by Kurt Vonnegut's widow, Jill Krementz, virtually all of the images in the book are from Wong's personal collection garnered over the years, many of the items from Nelson's personal collection, bits of it purchased by Wong when Nelson was strapped for cash. And the interview definitely lives up to its billing, covering, as it does, not just Macdonald's books and writing but a range of related subjects. I suppose one could call this the ultimate noir coffee table book. Because one could spend hours simply looking at its superb reproductions, and an equal number of hours reading it. Of course, you have to be a fan of Macdonald's fiction to fully appreciate it. And if you also happen to be one of those who also harbours a more than arcane interest in Paul Nelson's writing, It's All One Case is going to be irresistible. It's already in serious contention for my book of the year. A big book- with a short forward by the great Jerome Charyn- in more ways than one, and worth every penny.